Famous Paintings of the Catskills

Hudson River School Art Trail, New York

Walk in the footsteps of the painters who created the first great American art movement.

From Cedar Grove, The Thomas Cole National Historic Site

The Hudson River School Art Trail is a three-mile historic theme trail is part of a larger network comprised of seven sites linking the home of Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School, with painting sites that inspired the work of many artists in the nineteenth century. Thomas Cole's home is now a National Historic Landmark and today provides an orientation for your exploration of the Hudson River School Art Trail.

|

|

| The home and workplace of Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School of art, in Catskill, NY |

The Development of the Trail The Art Trail is currently in the initial stages of its development, which includes the creation of a brochure and web site with maps, driving and walking directions, and printed representations of the painted views to use as a comparison with today's actual views.

The Art Trail will include wayside interpretive signs including reproductions of paintings depicting that site as well as background information on the painting, the artist, and how the scene has been preserved. These wayside interpretive signs will serve as "captions on the landscape," enhancing the visitor's understanding about the Hudson River landscape and the art that it inspired.

The artist Thomas Cole made his first trip up the Hudson River to Catskill in 1825. The resulting paintings created a sensation in the nascent New York art world and launched the Hudson River School of art. These influential first paintings included a rendition of Kaaterskill Falls as well as South Lake, both of which are included in this Trail.

|

|

| Frederic Church, Scene on Catskill Creek, 1847 |

As one example of the sites along the trail, the painting at left was painted by Frederic Church at Trail Site 3 on the Catskill Creek Just a few miles from his home, this scene inspired Thomas Cole so much, he painted it more than any other. "The painter of American scenery has indeed privileges superior to any other; all nature here is new to Art." -- Thomas Cole, Journal entry, 1835

A New Art Movement... for a New Nation

In the early years of the 19th century, the fledgling American nation was seeking a cultural identity apart from Europe and a style of art that it could call its own. A group of artists found the answer in the beauty and majesty of the natural world they encountered in the Hudson River Valley and created magnificent landscape paintings. This movement, the first in American art, became known as the Hudson River School.

|

||||

The Hudson River School painters believed art to be an agent of moral and spiritual transformation. In large-scale canvases of dramatic vistas with atmospheric lighting, they sought to capture a sense of the divine, envisioning the pristine American landscape as a new Garden of Eden.

The Hudson River School Art Trail pays homage to both the creative and the historical significance of the Hudson River School painters. Their work created not only an American art genre, but also a deeper appreciation for the nation's natural wonders, laying the groundwork for the environmental conservation movement and National Park System.

The Hudson River School Art Trail enables you to walk in the footsteps of Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, Asher B. Durand, Jasper Cropsey, Sanford Gifford and other pioneering American landscape artists, and appreciate their work in an entirely new way. Most of the stops on the trail are within 15 miles of Cedar Grove, The Thomas Cole National Historic Site. Located in Catskill, New York, this was the home and studio of Thomas Cole, acknowledged founder of the movement. Wear comfortable shoes, open your eyes, and prepare to be inspired

Follow the Hudson River School Art Trail to the places that stimulated a distinctly American artistic identity. Seeing the sites on the Hudson River School Art Trail will be a memorable and rewarding experience, but be prepared to give it some time as the trail stops are located over a fairly wide area. Some of the stops are easy to get to by car, while others can be reached only on foot and range from an easy walk to a fairly strenuous hike. The Trail Map and Directions will help you to plan your visits to the sites you want to see.

|

|

| Thomas Cole, Lake with Dead Trees (Catskill), 1825 (click painting to enlarge) |

Cedar Grove - Thomas Cole National Historic Site

The Main House and Studio are open by guided tours, which are offered Friday, Saturday & Sunday, 10 am to 4 pm, from early May through late October. The grounds are open free of cost, and a small fee is charged for the tour. For detailed information about hours, admission and group tours, log on to www.thomascole.org.

Olana State Historic Site

Tours of the house are offered daily (except Mondays), 10 am to 5 pm, April through November, and on weekends and by appointment from December through March. Reservations to tour the house are highly recommended. There is a small fee per car on weekends and holidays, and a year-round fee for the guided house tour. For more information, log on to www.olana.org or call 518-828-0135.

North-South Lake Area

Your hike may require the purchase of a day-use fee at the New York State DEC's North-South Lake Campground, which is open from early May through late October. For information during the camping season, call the campground office at 518-589-5058, or call the DEC Regional Office year-round at 518-357-2234.

The Hudson River School Art Trail is a project of the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, presented in partnership with Olana, the home and workplace of Frederic Church, and with the National Park Service Rivers & Trails program, with assistance from the Greene County Tourism Promotion Department. The Trail project is funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation, with special thanks to Congressman John Sweeney for his support.

For more information:

The Hudson River School Art Trail is a project of Cedar Grove, The Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Spring Street, Catskill, New York 12414

Phone (518) 943-7465

www.thomascole.org

The National Recreation Trails Program

American Trails, P.O. Box 491797, Redding, CA 96049-1797 • (530) 547-2060 • Fax: (530) 547-2035 • [email protected] • www.AmericanTrails.org

A Primer On Gas Well Gold Rush

A primer on gas well gold rush

From the Marcellus Shale to horizontal drilling

The River Reporter, 08-02-28

NEW YORK & PENNSYLVANIA - Agents of corporate natural gas companies have been knocking on doors throughout the area.

These independent contractors are asking property owners to sign leases that will allow gas companies to explore for natural gas, which is believed to be beneath the local land mass in large deposits.

According to the experts, there are three main reasons why this is happening.

First, the cost of oil has been steadily rising over the last few years, reaching the unheard of price of $100 a barrel. By contrast, the cost of natural gas from a local well is much cheaper.

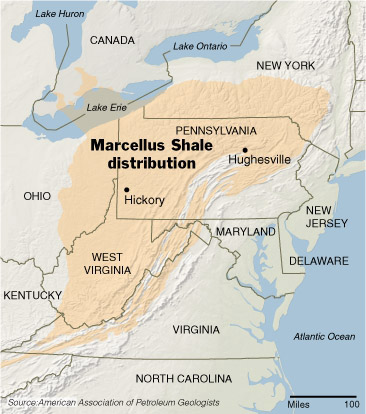

Second, geologists are telling the industry that there is evidence that very large deposits of gas are contained in a geological formation called the Marcellus Shale, which extends from Tennessee northward into central and northeastern Pennsylvania, including Wayne County, and the Southern Tier of New York State, including Sullivan County.

Third, new drilling techniques, principally developed by Halliburton, called horizontal drilling, can now recover gas deposits that were unrecoverable a short time ago.

No well permits have been given in Wayne County, but 14 wells have been created in Susquehanna County, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Also, no permits have been issued in Sullivan County, where the process of gas exploration got a later start.

Marcellus Shale

SUNY professor Gary Lash and his partner, Penn State professor Terry Engelder, are studying what they believe could increase national gas reserves by upward of 20 to 25 percent.

“It’s a unit called the Marcellus Black Shale, and we’ve been looking at the way it’s fractured as a means of extracting the natural gas from it,” Lash said. “The United States Geological Survey has predicted two trillion cubic feet of natural gas in this Marcellus deposit. Our estimates are perhaps as high as 500 trillion cubic feet.”

“The value of this science could increase the net worth of U.S. energy resources by a trillion dollars, plus or minus billions,” Engelder said.

Drilling techniques

While the estimated figures of available natural gas sounds great, the trouble has been the extraction process and the science behind it, Lash said.

The gas is trapped in microscopic spaces in rock formations, he said, and that’s where the horizontal drilling comes in. After drilling straight down to a certain depth, the drill is turned sideways in order to drill perpendicular to naturally occurring vertical fractures in the rock. “Then,” said Lash, “what they do is they pump fluids down into the well to pressurize the rocks, causing them to crack, and that allows the gas to migrate upward through a complex piping system that is installed after the drilling.”

A drill can be as deep as 7,000 feet. It takes about 660,000 to one million gallons of water for each well. The DEP issued 7,241 well permits throughout Pennsylvania in 2007, according to Ron Gilius of the DEP’s Oil and Gas Management Department.

With the drilling taking place horizontally, one question being asked by residents who do not sign leases is if the company gets gas from under their property, what happens to their rights? “Horizontal drilling under a property where the company does not possess a lease is a trespass,” said Stephen Rhoads, president of the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Association. “It’s illegal for them to do that.”

A landowner who signs a lease will get a bonus, a rental fee and, if gas is discovered, will receive a royalty of about 12.5 percent of the value of the gas. Some landowners have been able to negotiate the royalty to 18 percent. Bonuses and rentals are usually $5 per acre per year for five years.

Moving the gas from the ground to the refineries

Any gas recovered from wells must be transported to major gas lines such as the Tennessee Pipeline in Pennsylvania or the Millennium Pipeline in New York to be sold to the public.

The agencies that regulate the smaller pipelines, which take the gas to the major ones, are the state public service commissions (PSC), not agencies like DEP or DEC, according to Rhoads. But the PSCs do not regulate a third class of pipelines, the gathering pipes.

“There are gathering pipelines that merely take the gas to a holding tank or to another line coming from a well,” Rhoads said. “These are handled by the regulating agency like the DEP and the DEC.”

Several meetings have been held

The Penn State Cooperative Extension has held several meetings in Wayne County that introduced land owners to the vagaries of lease-signing, warning them that they must consult an attorney before they sign, preferably an attorney conversant with gas and oil drilling.

A group of landowners in Wayne County have formed an organization called the Northern Wayne Property Owners Alliance, which represents about 10,000 acres of land mass. The group will act together in the signing of any leases, according to leaders of the group. The organization has as its goals property protection, sensitivity to the environment and community, a contract that can be severed that includes increased compensation and royalties for landowners.

PA state senator Lisa Baker and state assemblyman Michael Peifer organized a public meeting with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to explain the permit process and the inspections of drilling sites. About 250 people attended that meeting on Wednesday, February 20.

There has been at least one meeting organized by Cornell Cooperative Extension for New York property owners, which brought in experts from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), who also explained the permit and inspection process of gas drilling.

A group of citizens opposed to the drilling, called the Damascus Citizens for Self-Government and Friends, has held two meetings. The last meeting introduced a speaker, Ben Price, director of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), who explained how his organization guided several Pennsylvania townships, helping them to pass laws prohibiting corporations from coming into their communities to carry out projects to which the community objected.

Some of the dangers to the environment, according to their website, are water contamination, decreased property values, soil contamination, depletion of the water table, increased heavy traffic and occasional pipe-line explosions.

There's Gas in Those Hills

There’s Gas in Those Hills

HUGHESVILLE, Pa. — At first, Raymond Gregoire did not want to listen to the raspy voice on his answering machine offering him money for rights to drill on his land. They want to ruin my land, he thought. But he called back anyway a week later to hear more.

By the end of February, he had a contract in hand for $62,000, and he pulled together a group of 75 neighbors who signed $3 million in deals.

“It’s a modern-day gold rush in our own backyard,” Mr. Gregoire said.

Not just his backyard either — a frenzy unlike any seen in decades is unfolding here in rural Pennsylvania, and it eventually could encompass a huge chunk of the East, stretching from upstate New York to eastern Ohio and as far south as West Virginia. Companies are risking big money on a bet that this area could produce billions of dollars worth of natural gas.

Not just his backyard either — a frenzy unlike any seen in decades is unfolding here in rural Pennsylvania, and it eventually could encompass a huge chunk of the East, stretching from upstate New York to eastern Ohio and as far south as West Virginia. Companies are risking big money on a bet that this area could produce billions of dollars worth of natural gas.

A layer of rock here called the Marcellus Shale has been known for more than a century to contain gas, but it was generally not seen as economical to extract. Now, improved recovery technology, sharply higher natural gas prices and strong drilling results in a similar shale formation in north Texas are changing the calculus. A result is that a part of the country where energy supplies were long thought to be largely tapped out is suddenly ripe for gas prospecting.

Pennsylvania, where the Marcellus Shale appears to be thickest, is the heart of the action so far. Leasing agents from Texas and Oklahoma are knocking on doors, leaving voice mail messages and playing host at catered buffets to woo dairy farmers and retirees. They are rifling through stacks of dusty deeds in courthouse basements to see who has underground mineral rights to the deepest gas formations.

Pennsylvania, where the Marcellus Shale appears to be thickest, is the heart of the action so far. Leasing agents from Texas and Oklahoma are knocking on doors, leaving voice mail messages and playing host at catered buffets to woo dairy farmers and retirees. They are rifling through stacks of dusty deeds in courthouse basements to see who has underground mineral rights to the deepest gas formations.

Thomas B. Murphy, a Pennsylvania State University educator who runs a program to instruct landowners on their rights, estimated that more than 20 oil and gas companies will invest $700 million this year developing the Marcellus Shale. Up to one half of that will be invested in Pennsylvania, he estimated.

The cost to companies for leasing mineral rights jumped from $300 an acre in mid-February to $2,100 now. “It shows you the pace this is going,” Mr. Murphy said. “I would call it breakneck.”

The cost to companies for leasing mineral rights jumped from $300 an acre in mid-February to $2,100 now. “It shows you the pace this is going,” Mr. Murphy said. “I would call it breakneck.”

Dale A. Tice, a lawyer representing landowners in lease negotiations, said companies were on a “feeding frenzy.”

Industry experts say in the last three years companies like Anadarko Petroleum, Chesapeake Energy and Cabot Oil and Gas have leased up to two million acres for drilling in the region, half of that in the last nine months.

Whether their bets will pay off is by no means a sure thing.

Researchers at Penn State and the State University of New York at Fredonia estimate that the Marcellus has 50 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas, roughly twice the amount of natural gas consumed in the United States last year. But government estimates of the amount of gas recoverable from the Marcellus are relatively modest.

Researchers at Penn State and the State University of New York at Fredonia estimate that the Marcellus has 50 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas, roughly twice the amount of natural gas consumed in the United States last year. But government estimates of the amount of gas recoverable from the Marcellus are relatively modest.

Early test results have encouraged companies to keep drilling, but most are holding details of their test wells close to the vest.

The company that has done the most work is Range Resources of Fort Worth, which says it plans to invest at least $426 million in the Appalachia region this year.

The company has reported promising results from the first 12 wells that it has drilled horizontally, the technique considered by most experts to be the most effective in the Marcellus. The most recent six have each produced more than three million cubic feet of production a day in recent months, and company executives say that is better than the average for wells recovering natural gas in the Barnett Shale in north Texas.

“The Marcellus is important to Range and it could be important to the country but it really is still early,” said Rodney L. Waller, a senior vice president at Range. “I can build you a scenario where it can be significantly better than the Barnett but it’s a function of economics.”

Energy experts say the Marcellus, along with other smaller shale formations being developed around the country, is coming under scrutiny at an opportune moment, just when conventional domestic natural gas production and imports from Canada are diminishing. With easy-to-find gas fields in decline, the country will need to explore in deeper waters in the Gulf of Mexico and penetrate deeper under the surface on land.

If all goes well, the Marcellus could help moderate the steep climb in natural gas prices and reduce possible future dependence on natural gas from the Middle East, which is beginning to arrive at coastal terminals in liquefied form.

Natural gas in the Marcellus and other shale formations is sometimes found as deep as 9,000 feet below the ground, a geological and engineering challenge not to be underestimated. The shales are sedimentary rock deposits formed from the mud of shallow seas several hundred million years ago. Gas can be found trapped within shale deposits, although it is too early to know exactly how much gas will be retrievable.

The gas from all the shales combined “is a game changer,” said Robert W. Esser, an oil and gas expert at Cambridge Energy Research Associates. He estimated that shale produced four billion cubic feet of gas a day on average last year, or about 7 percent of national production, and that shale gas production would increase to nine billion cubic feet a day by 2012, or about 15 percent of expected national production.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority estimates that developing New York’s portion of the Marcellus could roughly double the amount of natural gas now produced in New York. Currently that is about 55 billion cubic feet a year, providing for 5 percent of the state’s needs.

The Marcellus has suddenly become attractive in large part because natural gas prices have spiked in the last several years and the geologically similar Barnett Shale has been an industry sensation.

By using horizontal drilling techniques, oil and gas companies have been able to draw natural gas from underneath the city of Fort Worth, even from below schools, churches and airports. The companies have perfected hydraulic fracturing techniques, pumping water and sand into well bores to fracture shale and release gas from its pores.

Production in the Barnett has exploded from a trickle five years ago to over three billion cubic feet a day, and energy experts say that number could more than double by 2015. Shale gas development in other parts of Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas has also shown promise.

But no formation compares in size to the Marcellus. It is deeply entrenched in wooded and mountainous countryside and expensive to reach. But the reserve is also within short pipeline distance from some of the nation’s most energy-hungry cities.

Still, not everyone here is happy about all the leasing and drilling. At meetings with the companies, landowners have asked questions about potential hazards to water and woodlands.

Keith Eckel, 61, a grain farmer with 700 acres in northeastern Pennsylvania, said he had not decided whether to let the companies drill on his property. “Farmers have taken care of this land all their lives and don’t want to see it destroyed,” he said.

But many farmers and retirees in rural Pennsylvania appear excited that their lives are about to change.

“Now I can retire,” said Robert Deiseroth, a 63-year-old farmer and auctioneer from the town of Hickory, who recently received a $16,000 royalty check from Range Resources that he hopes will be repeated month after month. “This was a godsend for me. If it weren’t for this I would have to sell off some of my land to get some money for retirement.”

Mr. Deiseroth has put new windows in his house, bought a new fishing boat and plans to build a new garage. His 89-year-old father and 90-year-old mother, who live nearby, just got a $20,000 monthly check. His father has replaced the golf cart he drove around his farm with a Kubota utility vehicle, while his mother has bought a flat-screen television.

“When Range came in a lot of people didn’t like it,” Mr. Deiseroth said, “But things changed when they started getting their checks.”

History of the Catskill Park and Forest Preserve

- Written by Norm Van Valkenbergh; compiled and edited from various sources by Chris Olney; with some additions by Chris Olney

original link is here:

http://www.catskillpark.org/history/forest.htm

The history behind the creation, purpose, and evolution of the Catskill Park and Forest Preserve is not fully understood by many. To learn the context of how the Catskill Park and Forest Preserve came to be, one has to look at what was going on in the Adirondacks and in the State Capitol during the 1700's and 1800's.

In the early years of New York State, and indeed the nation, the State was the owner of several million acres of forested land. Following the Revolutionary War, in 1779, the new State's fledgling legislature passed what was referred to as the 'Act of Attainder' law, officially transferring all lands owned by the Crown of England as of July 9, 1776 to the people of New York. The same act also voided the land titles of those who had remained loyal to the Crown during the fight for independence and declared those lands to be owned by the State. These lands amounted to approximately seven million acres and were mostly in the Adirondacks, covering that entire large region. In other parts of the State, huge tracts of land had been patented away by the Crown to individuals long before and were now mostly settled. This was especially true in the Catskills where Queen Anne had granted one and a half million acres to Johannes Hardenbergh and his partners on April 20, 1708. The State therefore inherited little or no land in the Catskills when the Act of Attainder was passed.

There was little or no preservation sentiment this early on, and settlement and industry were the primary motivating social forces of the times. The young state government had little revenue to keep it functioning this early on, and public officials seemed bent on getting rid of the millions of acres of land the State now held in the Adirondacks; a seemingly inexhaustible supply of natural resources. Early state legislatures, beginning in the 1780's and continuing for over 50 years, passed a series of laws designed for easy disposal of the "waste and unappropriated lands" of the Adirondacks. They sold off public land to private individuals for one shilling per acre, and exempted those lands from state taxes for a seven year period. The single largest of these land grants was made to Alexander Macomb in 1792, when the State sold 3,635,200 acres to Macomb for "a generous eight pence per acre." Most of the buyers, however, were logging and railroad companies who were interested in turning a quick profit from cutting and selling timber. By the early 1800's the lumbermen had exhausted most of the easily accessible tracts in the flatlands and began to move up into the greener areas of the surrounding mountains. The State succeeded in getting rid of its Adirondack land, conveying nearly all of it by about 1820. Private landowners also often succumbed to the pressures of the logging companies when they could no longer deal with the burden of property taxes. After the profitable trees and other resources were removed, the companies usually then got out and allowed the land to return to the State for unpaid property taxes. Much of that land returned to public ownership far depleted in value after the removal or other destruction of the forest resource.

While the logging industry was the worst offender in the despoliation of the forests, other enterprises were also to blame. The tanning industry, especially in the Catskills, wiped out hemlock trees to the extent that tanneries were forced to give up the business because of the lack of readily available hemlock bark. The paper industry seriously depleted the spruce, pine, basswood, popple, and white birch. The charcoal industry thrived on clear-cutting the area of its operation. The forested area of New York's mountains was also decreased by major fires caused by careless lumbermen. Timber thieves stripped the unprotected state-owned lands. And of course the forests were further encroached upon by the settlements and farms that expanded into the interior of both the Adirondacks and the Catskills in the early 1800's. Following a tour of the United States in 1831-32, French nobleman Alexis de Tocqueville wrote of his observations and impressions; "In Europe people talk a great deal of the wilds of America, but the Americans themselves never think about them; they are insensible to the wonders of inanimate nature. Their eyes are fired with another site; they march across these wilds, clearing swamps, turning the courses of rivers…" Later, in the 1850's, the state legislature gave the railroad companies the right to purchase many thousands of acres of the remaining State lands, leaving only the inaccessible mountain peaks and passes in the distance.

The fish and game of the mountains were treated with the same careless abandon as the forests themselves. Early journalists and authors, after visiting the Adirondacks and Catskills, wrote of the seemingly infinite supply of sport that could be had in those areas. Stories of catching 120 pounds of trout in two hours, of shooting five deer in one month, or of catching a 19-pound trout were not uncommon and were no doubt true, because there were no laws prohibiting such excessive harvests of fish and game. Tales such as these brought hunters and fishermen to the mountains in droves with the inevitable result that by 1820 the last trout was gone from Saratoga Lake; by 1822 the wolf had disappeared; the moose, elk, and panther disappeared; no more 19-pound trout were reported. Hotels and spas sprang up in what forests were left, serviced by extensive new railroads, and by 1850 America's first wilderness was no more.

But popular attitudes about nature slowly began to change in the early to mid-1800's, and a romantic movement began to idealize nature and provide a voice to counter our culture's steady consumption of natural resources and degradation of natural systems. Famed painter Thomas Cole began painting idyllic scenes in the Catskill Mountains and Hudson Valley in the 1820's, and in 1839 Charles Cromwell Ingham, founder of the National Academy of Design, first exhibited his oil painting of "the Great Adirondack Pass" inspired by a geology survey he participated in two years earlier. Such works began a tradition of Adirondack and Catskill landscape painting that would be popularized by the 'Hudson River School' of landscape painters who came after them.

Dr. Elliot Vesell, scholar of the Hudson River School, writes, "The work of the Hudson River School represents the first, and perhaps the last, systematic attempt to depict on canvas a unified vision of the American landscape. It celebrated the wonders of nature in this country by elaborately describing the facts of natural landscape and by presenting seemingly endless vistas through clear uncontaminated air." Vesell maintains that what the dozen or so artists of the Hudson River School shared was "a common spirit of devotion to nature and a common background of aesthetic ideas", and that their collective achievement in the mid-1800's was "to present a new view of nature and of man's relationship to nature which had widespread ramifications in American literature as well as in other aspects of American culture."

The paintings of the Hudson River School, along with the writings of authors and poets such as James Fennimore Cooper, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thorough, and Walt Whitman, began to influence popular American conceptions about the value of nature. Vesell states that both the painters and writers of the early and mid-1800's generally "associated nature with virtue and civilization with degeneracy and evil", and summarizes that the basic message of popular nature writing of the time was that "Americans, particularly close to nature, were still virtuous, but with the march of civilization as measured by the progress of the axe through the forests, virtue would vanish, health would be destroyed, and the nation's personality lost." Author Peter Wild notes that Thoreau was one of the earliest advocates for setting aside wild lands and leaving them in their natural state, and as early as the 1830's artist George Catlin was advocating for a system of national parks. A growing urban population began to embrace the romanticism of nature and sought out beautiful places among the rivers and mountains to relax, recreate, and improve their physical and mental health.

The importance of forests in the matter of water supply began to be recognized in the 1850's. Water, of course, was necessary for drinking purposes, and for the lumbering industry and most other businesses of that time it was the least expensive and most convenient mode of transportation. Early naturalists and scientists pointed out that continued depletion of the woodlands of important watersheds seriously endangered the maintenance of stream flows and hastened flooding and erosion of valuable topsoil. Some early writers and editors in New York finally recognized that it was time for action and called for a new Adirondack policy. S.J. Hammond, in his 1857 book Wild Northern Scenes, said of the Adirondacks, "Had I my way I would mark out a circle of a hundred miles in diameter and throw around it the protecting aegis of the constitution. I would make it a forest forever." George Dawson of the Albany Evening Journal said much the same thing in editorials of the late 1850's, and in an 1864 editorial of the New York Times, Henry J. Raymond asked that concerned citizens get together and "seizing upon the choicest of the Adirondack Mountains, before they are despoiled of their forest, make of them grand parks owned in common ..."

It was also in 1864 that George Perkins Marsh published Man and Nature; or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. This work is essentially one of the first textbooks on ecology, and in it Marsh describes the relationship of one part of the environment to another, and how the influences of man impacts that relationship. Marsh singles out forestland in particular as critical for holding together other important components of a natural landscape. The book did not specifically address New York State, however it became a foundation and influencing factor for others arguing for the New York Forest Preserve in later years. People with scientific backgrounds gradually began to join the battle for forest protection in New York. Franklin B. Hough, a doctor and noted historian from Lewis County, who in 1881 became the first chief of the Federal Division of Forestry (forerunner to the U.S. Forest Service), traveled the backcountry of the Adirondacks directing the 1865 state census. He was appalled at the condition of the forests and was scientist enough to realize the disastrous results that could occur if denudation of the watersheds was allowed to continue. He began to preach the need for adoption of forest conservation practices, and he used his influence with friends in government to arouse public sentiment for his cause. Famed landscape architect and proponent of wild parks, Frederick Law Olmstead, also advocated the setting aside of land to protect the Adirondacks.

Conservationist John Muir and the Catskill's own nature essayist, John Burroughs, carried on the American popularization of nature in the latter half of the 19th century. Such authors, according to Peter Wild, "saw their souls reflected in America's wildlife and woodlands. To them, setting aside forests as unexploited wholes often took on a religious imperative. Their books and articles in magazines stirred the public to re-evaluate its long-ignored wild heritage." Similarly, sportsmen's groups and various hunting and fishing periodicals began the fight for a better system of game laws and game management in the 1860's and 70's. George Bird Grinnell, paleontologist, naturalist, and editor of the popular publication Forest and Stream, would later argue continually in the final decade of the century for sound forest management in the Adirondack Forest Preserve. Despite the formation of the Commission of Fisheries in 1868, the State's first natural resources-related commission, individuals eventually took matters into their own hands by buying large tracts of land and forming private fishing and hunting clubs. Trout fishing historians Austin Francis (in his book "Catskill Rivers") and Ed Van Put (in his book "The Beaverkill") tell the stories of several such fishing clubs here in the Catskills. Noted angling clubs such as the Willowemoc Club became established in 1868, the Salmo Fontinalis Club in 1873, the Beaverkill Association (later the Beaverkill Trout Club) in 1875, the Beaverkill Club in 1878, the Balsam Lake Club in 1883, the Fly Fishers Club of Brooklyn in 1895, and the Tuscarora Club in 1901.

The economic motives of powerful businessman of the time were almost as strong as the motives of conservationists for forest and watershed protection in New York's mountain areas. Peter Wild notes that business groups such as the Manufacturer's Aid Association of Watertown were big supporters of the creation of a New York forest preserve "because of industry's dependence on a steady supply of water power, which only healthy forests could provide", and that "business leaders in New York [City] recognized the link between the city's growth and nature. They fretted about sufficient drinking water but also about how to keep the Erie Canal full, their economic lifeline."

Verplanck Colvin, an Albany man trained in the law and a self-made land surveyor, first visited the Adirondacks in 1865 and "was amazed at the natural park-like beauty of this wilderness", and began suggesting the preservation of the remaining wilderness areas as a state park. On October 15, 1870, Colvin climbed Mt. Seward in the Adirondacks, and recorded that "the view hence was magnificent, yet differing from other of the loftier Adirondacks, in that no clearings were discernable; wilderness everywhere; lake on lake, river on river, mountain on mountain, numberless." It was at this place, and at this time that the Forest Preserve of New York State started on the path toward reality. Following his trip, Colvin said in the 24th Annual Report of the New York State Museum of Natural History that "… these forests should be preserved; and for posterity should be set aside, this Adirondack region, as a park for New York ..." No mention was made of the Catskills. The forest protection ideas of Colvin and Hough, who met each other at meetings of the Albany Institute (a respected literary and scientific society), were well received by people who saw the need for a more reliable and clean water supply for Albany, possibly from the Hudson River emanating from the Adirondack Mountains.

The State legislature was paying attention to Albany's recent drought and water supply problems, and out of it all came an 1872 law (Chapter 848) that established "A commission of State parks ... to inquire into the expediency of providing for vesting in the State the title to the timbered regions lying within the counties of Lewis, Essex, Clinton, Franklin, St. Lawrence, Herkimer and Hamilton, and converting the same into a public park." The Commissioners, in reporting their results to the 1873 Legislature, said "… we are of opinion that the protection of a great portion of that forest from wanton destruction is absolutely and immediately required."

The report outlined the scarcity of settlements in the area and pointed out the disastrous effects that mining, tanning, lumbering, and forest fires had had on what was once a vast tract of virgin forest. The report deplored the early sales of land to private individuals for nominal sums and the outright grants of huge tracts to railroad companies. It tabulated the public acreage in those Adirondack counties, as of the date of the report, to be 39,854 acres, and noted that this was only a small fraction of the land holdings that had been vested in the public at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. The report elaborated that the State of New York contained some of the most remarkable watershed areas in eastern North America, with the St. Lawrence River on the north, the Great Lakes on the west, the Allegany River on the south, and the Hudson on the east. The report did not recommend that the Adirondack forests be preserved forevermore, but it did recommend that consideration should be given to the utilization of the forests as a product or crop. It expounded on the value of boating, camping, hunting, and fishing "to strengthen and revive the human frame … to afford that physical training which northern America stands sadly in need of." It further pointed out the health-giving values of having a wilderness area accessible to a large population. It is worth noting that in this first official study the concepts of preservation, management, and recreational development were largely treated as compatible and simultaneously attainable.

Unfortunately, not much came of that report and opinion. However in 1874 Assemblyman Thomas Alvord introduced a bill entitled "AN ACT to create and preserve a public forest, to be known as the Adirondack Park." The bill though did not have a Senate sponsor and progressed no further. In 1876, the State Legislature did pass a law (Chapter 297) prohibiting "the disposal of any part of the public lands on Lake George or the islands thereof." In 1882 Governor Alonzo Cornell, in his message to the legislature, condemned the State's policy of selling its wild lands. He suggested that the uses of the Adirondacks should be carefully restricted. Similarly, Governor Grover Cleveland said in his 1883 message to the State Legislature that the Adirondack forests should be preserved, and that the present state lands and all other lands "it may hereafter acquire" should be declared "to be park lands."

All of the pressure being brought about by public officials, individuals, and the public-at-large began to take effect in 1883. In that year the Legislature passed a law (Chapter 13 of the Laws of 1883) prohibiting the sale "of lands belonging to the State situated in the counties of Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Fulton, Hamilton, Herkimer, Lewis, Saratoga, St. Lawrence and Warren", these being the seven counties inquired into by the 1872 Commission, plus Warren County, which includes Lake George, and the two additional counties of Fulton and Saratoga. Another law passed that year (Chapter 470) also helped lay the groundwork for the future Forest Preserve, by granting the Comptroller the authority to spend up to $10,000 to purchase forest lands with unpaid taxes in the Adirondacks - the first such appropriation. The foundation for the Forest Preserve was being laid, but the Catskills were not going to be a part of it. Or so it seemed.

With the enactment of the laws stopping the sales of Adirondack lands, it appeared that the State was going to continue to be a major landowner. Furthermore, additional lands were coming to the State for unpaid taxes and through partition sales. The time had finally come to provide some sort of management and protection to its ownerships. Accordingly, the deficiency budget of 1884 appropriated $10,000 to the Comptroller for "… perfecting the state's title to such lands; of definitely locating, appraising and examining them as may be required; of protecting them from trespassers or despoilers and prosecuting all such offenders, and generally of guarding, preserving the value of and protecting such lands …" The same budget (Chapter 551 of the Laws of 1884) provided $5,000 to the Comptroller "for the employment of such experts as he may deem necessary to investigate and report a system of forest preservation ..." Here now the Catskills had a chance at protection because these 'experts' were not confined to any single geographic area or list of specific counties.

The 'experts', or Commissioners as they called themselves, were led by Professor Charles Sprague Sargent of Harvard University, the country's premier dendrologist at that time. The Commission reported to Comptroller Alfred C. Chapin on January 23, 1885, saying that they had "devoted themselves industriously to the study of the question." They had visited the Adirondacks a number of times, had "caused a detailed examination of the position and condition of the Adirondack forests to be made by trained forest experts", and were convinced that something certainly did need to be done to preserve the forests. They noted the continued plundering in the Adirondacks that "reduces this whole region to an unproductive and dangerous desert." The Commission noted the advantages of a continuing forest on the flow of water and outlined the forest as a natural recreational area to be enjoyed by the people. It laid the blame for the destruction of the forests to the charcoal and lumber industries, the construction of numerous small reservoirs throughout the mountains, and forest fires. It pointed the finger of accusation at the railroads and loggers for the vast number of fires that were helping to destroy the remaining trees.

The Commission 'experts' had also "visited the forest region of Ulster and Delaware counties," but were not much impressed. They said, "The forests of the Catskill region are not unlike in actual condition those covering the hills which mark the southern limits of the Adirondack plateau. The merchantable timber and the hemlock bark were long ago cut, and fires have more than once swept over the entire region, destroying the reproductive powers of the forest as originally composed and ruining the fertility of the thin soil, covering the hills. The valleys have now, however, all been cleared for farms, and forest fires consequently occur less frequently than formerly. A stunted and scrubby growth of trees is gradually repossessing the hills, which, if strictly protected, may sooner or later develop into a comparatively valuable forest. The protection of these forests is, however, of less general importance than the preservation of the Adirondack forests. The possibility of their yielding merchantable timber again in any considerable quantities is at best remote; and they guard no streams of more than local influence. Their real value consists in increasing the beauties of summer resorts, which are of great importance to the people of the State."

The Commissioner's report recommended that the State not enter into the acquisition of additional lands by condemnation, but rather to initiate an acquisition program based on purchases, which would be better received by the public. It stated however, that there would be no benefit to purchasing additional lands if past poor management practices were to continue. The commissioners recommended that a forest commission be set up to create regulations and policy for the administration of the public lands. The report went on to recommend legislation establishing a Forest Preserve of "all the lands now owned or which may hereafter be acquired by the State of New York" to the ten Adirondack counties listed in the 1883 law and the additional county of Washington, with such lands to "be forever kept as wild forest lands." A second law was recommended to amend the penal code to set forth punishments for violations relating to forest destruction, and a third law was recommended to provide that the lands of the Forest Preserve would be taxable for all purposes.

The Comptroller was willing to accept and endorse all of this, and submit the recommendations to the state legislature for action. So the Catskills were not intended to be included in the new Forest Preserve after all. Comptroller Chapin, however, had not fully reckoned with the likes of Cornelius Hardenbergh. The fact that the State land "now owned or which may hereafter be acquired" in the Catskills did become part of New York's Forest Preserve, and subsequently that a Catskill Park was created, all had to do with the tenacity of Hardenbergh and a complicated series of laws dealing with property taxes (and the non-payment of them).

Cornelius A.J. Hardenbergh [see figure] was a bachelor, farmer, merchant, and public servant - not necessarily in that order. He owned and operated a 110-acre farm on the northerly bank of the Shawangunk Kill at the point where the stream formed the southerly boundary of the Town Shawangunk and the line between Ulster and Orange Counties. He picked up his mail in Pine Bush, just across the kill in Orange County, but he resided in Ulster County. Hardenbergh was an avowed opponent of taxes. When a tax was to be imposed on his wheel-making shop and business in the early days of the Civil War, he closed his shop rather than pay the tax. An admiring public elected him supervisor of the Town of Shawangunk, and then served on the Board of Supervisors of Ulster County, sometimes as its chairman. It was in this capacity that Hardenbergh became involved in a running battle with State Comptroller Chapin and his predecessors over state taxes being assessed against the lands acquired by the county at tax sale. No matter that Ulster County was not being treated any differently from any other county in the state, Hardenbergh opposed such taxation by the State.

In the 1870's, a succession of laws were passed requiring county treasurers to collect all taxes levied on lands for state or county purposes. These laws further required the counties to pay the state taxes by the first of May each year whether the treasurers had been able to collect them or not. Ulster County was added to the list of counties subject to these requirements by Chapter 200 of the Laws of 1879. If that wasn't bad enough, Chapter 371 of the Laws of 1879 was passed a month later to restate, word for word, the same provisions as were in Chapter 200, allegedly enacted to correct a minor error in the title of the first law. If Hardenbergh wasn't incensed the first time around, he surely was at the passage of the second law. Then came Chapter 382 of the Laws of 1879, which provided that the Comptroller would issue a deed to the counties for each parcel of land not redeemed or sold at the 1877 tax sale. That law further required that the counties were liable for the current unpaid taxes on these lands, as well as for later taxes that would come due. If the counties didn't pay the taxes in ninety days, then interest at the rate of 6% would be added.

The Comptroller at this point was holding the winning hand. Hardenbergh, however, saw to it that Ulster County did not pay the Comptroller's bills. He won a minor point when he influenced the passage of Chapter 573 of the Laws of 1880. This law restated the procedures for publishing notices of pending tax sales as such procedures had been set out in the 1879 laws. There was one change. The earlier laws had said, "the publishing of the said notice not to exceed the sum of two dollars for each newspaper so publishing each of the several notices..." The 1880 law contained the same wording but added, "excepting in the county of Ulster, wherein the sum shall not exceed one dollar."

The next round also went to Hardenbergh. The last 1879 law had provided that after the state acquired title to unredeemed and unsold lands, the Comptroller would deed these lands to the respective counties. Chapter 260 of Laws of 1881 changed that for Ulster County only. This law said that, "should there be no purchaser willing to bid the amount due on the lot or parcel of land to be sold," then the Ulster Country treasurer could bid on the "lot or parcel of land for the county." He then, and not the Comptroller, would issue the deed to the county or, if so directed by the Ulster County Board of Supervisors, he could sell the land. Other provisions of this law clearly set out the battle lines. One section stated, in referring to the earlier laws, "Where any authority is given or duly enjoined by those laws on the comptroller of the state, the same authority shall be exercised and the same duty shall be devolved on the county treasurer of Ulster County." One of the final sections of the law provided that lands acquired by Ulster County for unpaid taxes "shall be exempt while so owned by said county from all taxes" and directed the treasurer "to strike such land from the tax roll ..." Finally, it repealed, "All acts or parts of acts inconsistent herewith, so far as the county of Ulster is affected ..."

The Comptroller won the round after that. Chapter 402 of the Laws of 1881 was passed just two weeks after Chapter 260. It repeated many of the provisions of the 1855 law, on which all of the later laws had been based. While not ever mentioning Ulster County, the language of the law makes it clear to what county it was directed. The listing of counties required to turn over delinquent tax lands to the Comptroller for sale, which did not include Ulster County, was followed by the phrase, "or any other county for which there may, at the time, be a special law authorizing and directing the treasurer thereof to sell 'lands of non-residents' for unpaid taxes thereon ..." That, of course, meant Ulster County. This latest law put things back the way they were. The Comptroller was directed to issue deeds to the counties for unredeemed and unsold lands. The final provision of the law stated, "All acts and parts of acts inconsistent with the provisions of this act are hereby repealed."

The Comptroller was still ahead with the passage of Chapter 516 of the Laws of 1883. This law set out what was to happen to the lands not sold on the 1881 tax sale. It included Ulster County again not by name, but by the "all other counties" phrase. Again, the Comptroller was to issue the deeds to the counties and the counties would be liable for taxes due and 6% interest if the Comptroller's bills were not paid. In the case of Ulster County, they weren't. By this time, in fact, the county was in arrears some $40,000. From his vantage point on the fringe of Ulster County, Hardenbergh needed someone "in high places." In 1879, the year when Ulster County began to run up its tax bill under the provisions of the laws detrimental to its interest, one of those representing the county was a freshman Assemblyman, George H. Sharpe from the City of Kingston. In that year all three Assemblymen from Ulster County were freshmen, still novices at the devious routes of lawmaking. In 1880, when it appeared that Ulster County was on the verge of getting the upper hand, Sharpe had become Speaker of the Assembly. It was he who had successfully moved Chapter 260, Ulster County's high point in the battle, through the legislative process. He was unable, however, to forestall the passage of Chapter 402. In 1882, a quiet year for Ulster County and its tax problems, Sharpe was serving his last year as an Assemblyman and was no longer Speaker. He had, however, provided good service to his Ulster County constituency.

Another freshman Assemblyman took his seat in 1882. Alfred C. Chapin, representing Kings County, would later become the last mayor of the independent City of Brooklyn and would preside over its amalgamation into the City of New York at the turn of the century. Speaker of the Assembly when Chapter 516 was enacted in 1883, he became Comptroller the following year. It was he who would do the final battle with Hardenbergh, who was elected Assemblyman at the November 1884 general election. Now Hardenbergh would carry his own bills, and he wasn't long in making himself known. Early in the session, influenced by the 1883 law prohibiting the sale of state lands in the eleven Adirondack counties, he introduced a bill to prohibit the state from selling its land in Ulster County also. It didn't get anywhere. Undeterred, he and his Ulster County colleague, Assemblyman Gilbert D. B. Hasbrouck of Port Ewen, went to work on a bill that was enacted on April 20, 1885 - about the same time that Comptroller Chapin was receiving the report of the 'experts' investigating "a system of forest preservation."

Chapter 158 was a sweeping piece of legislation. It repeated, by listing every one of the 1879, 1880, 1881 and 1883 laws "as the same in any wise relate to the county of Ulster" and relieved the county "from the operation of said laws." It directed the Comptroller to cancel all previous sales of lands to Ulster County under any of the repealed laws and to convey those lands to the state. Finally, and most importantly, it directed the Comptroller to give credit on his books to Ulster County for the principal and interest due on the lands that would be conveyed to the state. In one law, Ulster County was out from under its debt and its large tax sale land holdings were owned by the state.

Comptroller Chapin was supportive of the recommendation to create a forever wild Forest Preserve of the state lands in the eleven Adirondack counties. He even felt it only fair, as recommended by the report, that the state should pay taxes on these lands to the local governments where they were located. Hardenbergh had a particular ally in the Senate who also supported the creation of the Forest Preserve. Senator Henry R. Low, representing Orange County, was a near neighbor of Hardenbergh's, residing at Middletown, only fifteen miles south of Pine Push, on the banks of the Shawangunk Kill. Low had been a sponsor of the original bill recommended by the 'experts' and was a major participant in the conferences in which the final bill was written. He introduced the final bill in the Senate. The sponsor in the Assembly was James W. Husted from Peekskill in Westchester County, just across the Hudson River from Orange County.

And so it was that the New York State Forest Preserve was created on May 15, 1885, when Governor David B. Hill signed Chapter 283 of the Laws of 1885. This law established a three-person Forest Commission "appointed by the governor by and with the advice and consent of the senate" to have "care, custody, control and superintendence of the forest preserve." The Commission was empowered to "employ a forest warden, forest inspectors, a clerk and all such agents, as they may deem necessary ..." It stated (in Section 8) that, "The lands now or hereafter constituting the forest preserve shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be sold, nor shall they be leased or taken by any person or corporation, public or private." As had been recommended by the 'experts', this law defined the Forest Preserve as being, "All the lands now owned or which may hereafter be acquired by the state of New York, within ..." the eleven Adirondack counties except such lands in the Clinton County towns of Altona and Dannemora, in order to provide for the prison at Dannemora and the lands used by the prison for its wood supply. Tacked onto the end of the list of Adirondack counties, thanks to the political maneuvering of Cornelius Hardenbergh, were the three Catskill counties of Greene, Ulster and Sullivan. The Forest Preserve began with 681,374 acres in the Adirondacks, and 33,894 acres in the Catskills.

Hardenbergh was serving the second year of his term when Chapter 280 of the Laws of 1886 was enacted. This was the companion bill recommended by the 'experts' to provide for taxation of the state lands. It stated that all lands of the Forest Preserve "shall be assessed and taxed at a like valuation and at a like rate as those at which similar lands of individuals within such counties are assessed and taxed ..." It set out the procedures by which and the dates when the Comptroller was required to certify and the State Treasurer was required to pay annual taxes to the treasurers of the Forest Preserve counties. Thus, not only was Ulster County free from its tax bill, but from that time forward it has received taxes from the state on those same lands that had been involved in the battle.

Hardenbergh left the Assembly at the end of his two-year term and went back to Ulster County. Over the years, many have debated just who was the "father" of the Adirondack Forest Preserve. The favorite seems to be Verplanck Colvin, and rightly so. However, no such debate has asked who was the "father" of the Catskill Forest Preserve, probably because the Catskill Forest Preserve has just quietly existed without much controversy, and has therefore received less attention than its Adirondack counterpart. Those who know of Hardenbergh's involvement have debated his motives. Some say he was interested only in solving Ulster County's tax problems and took the way out offered by the times. Others say bringing the state lands of the Catskills into the Forest Preserve was his main goal and, in reaching that, he solved the tax problems. We probably will never know the answer, but the fact remains, whatever the motive, without Cornelius A. J. Hardenbergh, the people of New York State would not enjoy the benefits of a Catskill Forest Preserve. That is certainly reason enough to remember his place in history.

It took a few months to appoint the three-member Forest Commission. The first appointment was quickly made a week or so after the signing of the law - Theodore B. Basselin, a lumberman from Croghan in Lewis County with one of the largest timber cutting operations in the Adirondacks. It was not until September that the remaining two members were appointed; Townsend Cox, a New York City stockbroker from Glen Cove, Long Island and Sherman W. Knevals, a lawyer from New York City. They held their first meeting on September 23, 1885 and "took immediate steps to familiarize themselves with the duties and various interests intrusted [sic] to their charge." The preservation of forests was their principle objective, for the stated purposes of ensuring "the value of present and future timber; the value of forests as 'health resorts'; the conservation of sources of water supply; the increase of rainfall; and the climatic and sanitary influence of forests." They visited the Adirondack and Catskill regions. These visits were cursory only and they did not venture far from the main roads and villages. Instead, they hired "experienced, competent men … as special agents, who penetrated to every part of the wilderness."

In the case of the Catskills, the Commission did not really know what they had. After all, this addition to the Forest Preserve had been a last-minute political maneuver, and very little data existed as to the location of this state land asset. The Commission recognized in its first annual report that "the existence of the Catskill Preserve seems to be little known, although the State owns a large tract in the Catskill region." A tabulation of the state ownership did exist however, which indicated a total of 33,894 acres in the three Catskill counties. Greene County had 661 acres (507 acres in the Town of Lexington and 154 acres in the Town of Cairo). Sullivan County contained 502 acres (scattered in the Towns of Highland, Lumberland and Neversink). The remaining 32,731 acres was in Ulster County (with most of that being in the mountain Towns of Denning, Hardenbergh and Shandaken, principally on and around Slide Mountain). Most of this Catskill acreage was acquired by the State in the 1870's and 1880's as a result of tax sales and mortgage foreclosures. The Commission was quick to realize that the listing of Catskill counties was one short when they said, "The Catskill region occupies parts of four counties" and recommended a bill to add Delaware County.

The special agents who "penetrated to every part of the wilderness" came back with a different story than the 'experts' who had reported to Comptroller Chapin. The Catskill Forest Preserve, they said, "… is surrounded by the grandest of its scenery. Here the Slide Mountain rears its majestic form, surrounded by its retinue of lesser peaks. Here, also, are the deep, cool valleys, whose silence is broken only by the rushing cascades, or by the murmur of woodland sounds. Here are the rocky glens, among which the Peekamoose is so justly celebrated, while on every side the eye is greeted by an array of scenery unsurpassed throughout the State."

The streams also were "of more than local influence." The waters of the Schoharie Creek, they said, are "utilized as a feeder to the Erie Canal. ... The Esopus Creek ... pours its waters into the Hudson at Saugerties, affording an important water power, which is used to advantage by the manufacturers near its mouth. The east and west branches of the Neversink and the east branch of the Delaware all rise here, and flowing southward unite at Port Jervis and enter the Atlantic through Delaware Bay. ... Numerous mountain streams have become repopulated with trout, and now afford some of the best fishing in the State."

Even with that report, however, more needed to be known. In June of 1886, Commissioner Townsend Cox "penetrated" the interior of the Catskills himself when he climbed Slide Mountain, tallest peak in the Catskills. While Cox's trip was largely for political reasons, he did, in a meeting with reporters the following morning, stress the benefits of the Catskill Forest Preserve in maintaining the streams flowing from the area to form the rivers that were important to New York and its neighboring states.

In addition, the Commission "detailed Inspector Charles F. Carpenter to make a thorough examination of the Catskill Preserve." Carpenter stood fourth in line in the hierarchy of the staff employed by the Commission in 1886. Abner L. Train of Albany was secretary, Samuel F. Garmon of Lowville (Lewis County) was warden, William F. Fox of Albany was assistant warden, and Carpenter was the chief of two inspectors, drawing a salary of $125 a month. In addition, fifteen foresters were employed at $40 a month. All were headquartered throughout the Adirondacks except for one, Michael Hogan, who was stationed at Ellenville in Ulster County. Carpenter indeed made a "thorough examination" of the Catskill Mountains. His report covered 51 pages of the Commission's annual report for 1886. He first described the geography of the Catskills, their mountains, streams, lakes, ponds and soils. Then he detailed the forest cover of the area, deploring "the reckless waste going on all the time, and the noble forests mowed down to satisfy the cupidity of man …" He talked about the state lands composing the new Forest Preserve, and he too thought Delaware County should be added because "the State lands within that county are still under the control and management of the Commissioners of the Land Office and the State Comptroller. While this state of affairs exists the people of this county lose the benefit of the act ... which provides for the taxation of State forest lands in the counties embracing the forest preserve." After all, he said, "the State paid a tax of $638.25 for the year 1886" to Ulster County.

Carpenter knew of the fight waged by Ulster County over its taxes because he discussed the various laws that had been involved up to and including the act "passed April 20, 1885, just twenty-five days before the passage of the act creating the Forest Commission." All of it was, he said, "Through the enterprise of one or two citizens of Kingston an evidence of forethought and prudence, which from the earliest history of this region has always been justly attributed to the inhabitants of Wildwyk, now the city of Kingston."

Carpenter discussed the roads and highways and railroads that serviced the Catskills. He talked about the fine fishing and small-game hunting opportunities. He traced the history of the lumbering and tanning industries that had depleted the forests. He then described the "various industries" he had found "in making a tour of the counties embracing the Catskill forest preserve" town by town, village by village. He had, in fact, gone beyond the three counties, describing some industries in Delaware and Orange Counties as well. He was impressed by the Catskills, concluding that he had "rarely found ... an abandoned homestead ... This distinguishes this wild region from the similar one in the Adirondacks, where deserted homesteads are met at frequent intervals, and in places the dilapidated remains of whole villages ... The Catskill region as a whole has a good soil and friendly climate, which the Adirondacks can scarcely be said to possess."

After all that, one would have thought that the Catskills would have received some major attention from the Forest Commission. But it didn't. The Catskills slipped into the role of being secondary to the Adirondacks; a role that continues to this day. That may not be all bad, as any new idea is generally tried first in the Adirondacks and if it works, then it is applied to the Catskills, hopefully with all the quirks worked out. One beneficial result from the initial attention paid to the Catskills however, was the passage of Chapter 520 of the Laws of 1888, which added Delaware County to the county listing and made its 17,340 acres of state land a part of the Catskill Forest Preserve. Most of this land was south of the East Branch of the Delaware River and along the Ulster County line in the Towns of Andes, Colchester and Middletown. Also at this time was the first real attack on, and weakening of, the newly created Forest Preserve. Chapter 475 of the Laws of 1887 redefined a part of the duties of the Forest Commission and authorized the Commission to sell and convey "separate small parcels or tracts wholly detached from the main portions of the Forest Preserve and bounded on every side by lands not owned by the State, to sell the timber thereon, and to exchange these tracts for other lands adjoining the main tracts of the Forest Preserve." While this piece of legislation seems fairly definitive, it should be noted that no attempt was made to define the size of a "separate small parcel or tract." This law was presumably sponsored by the lumber interests, and it opened a crack in the door that had been slammed shut two years before. To some, it was not a good law; to others it was made to order. Significantly, it became a statute without the Governor's signature - he neither approved nor vetoed it in ten days and therefore it returned to the Legislature as law.

An Adirondack Park had been a concept talked about since the very first pleas were heard to do something about saving and preserving the Adirondack forests and mountains. An 1864 New York Times editorial by Henry J. Raymond had said, make "grand parks" of the "choicest of the Adirondack Mountains." Verplanck Colvin said, in speaking of the destruction of Adirondack forests in his 1870 report to the New York State Museum of Natural History, "The remedy for this is the creation of an Adirondack Park or timber preserve..." The 1872 Commission of State Parks was to look into converting the timbered regions of certain of the Adirondack counties "into a public park." Colvin, in his 1874 report to the Legislature on his "survey of the Adirondack wilderness," talked about the state acquiring all of the land in the High Peaks region of Essex, Franklin, and Hamilton counties and setting it aside as a park. He continued to be the chief proponent of the Adirondack Park idea during the 1870's and 1880's.

Throughout these times, those speaking of an Adirondack Park envisioned that all lands within the park boundary would be state-owned public land. By 1890, however, that concept was beginning to change. Governor David B. Hill, in his message to the Legislature of that year, thought a park should be outlined to include the "wilder portion of this (Adirondack) region covering the mountains and lakes" and, then acquire lands in that park area. Chapter 8 of the Laws of 1890 redefined the Forest Preserve by re-listing all of the counties that had been set forth the previous year (which had grown from the original listing to include Oneida County in the southwestern Adirondacks), but then it excepted form the Preserve all state lands within the limits of any incorporated village or city. Chapter 37 of the same year appropriated $25,000 to purchase lands in the Forest Preserve counties, which was the first such appropriation for the acquisition of lands to expand the Preserve. This same law also made reference to a State park as it might relate to the Forest Preserve lands.

The Forest Commission report for 1890 called attention to the existing scattered pattern of state land ownership and recognized that additions to this state land must come from purchases. It noted the public sentiment favoring acquisition and called for legislation to enable the state to acquire and hold state land in "one grand, unbroken domain." It stated that an advantage of increased ownership would be that greater control could be exercised against the railroads and trespass. The Commissioners revised their reasons for preserving forests to be for the "maintenance of timber supply; conservation and protection of watersheds; preservation and protection of fish and game; and the founding of a permanent public resort."

Notably, the 1890 Forest Commission Report included discussion on the subject of a proposed Adirondack Park. One of the most interesting parts of the report was the inclusion of a map of the Adirondacks on which a proposed park boundary had been delineated in blue. From that time forward, the phrases "inside the blue line" and "outside the blue line" have been used to describe lands inside and outside the Adirondack and Catskill Park boundaries. Unfortunately, the narrative of the report in regard to public ownership within a new Adirondack Park was contradictory. The commission seemed unwilling to say whether all lands inside the proposed park should be acquired by the State or not, so in different places in the text they said both. The report noted that it was unwise to proceed with acquisition of the entire Adirondack plateau, recognized the presence of villages and private clubs within the 'blue line', and concluded that proper forest management on private lands could be a compatible land use in the Park. But at the same time it said that all of the lands within the park boundary should gradually be acquired. There was also unclear language in regard to timbering on State lands inside and outside of the park boundary. The Commission felt that state lands outside of the park should be sold whenever those lands did not, in the opinion of the Commission, promote the purpose of the Forest Preserve, and the proceeds would then be used to buy additional lands inside the park. The Commission concluded by unanimously recommending the necessary legislation to establish and manage a park in the Adirondack wilderness, and state acquisition of title to all the forest lands within the limits of the park "which it is possible to acquire, in the shortest practicable time." Use of the word 'manage' would seem to leave the door open for the practice of forestry and lumbering on the State lands, and the use of the word 'forest' as an adjective modifying the word 'lands' suggests that it was the Commission's recommendation not to acquire non-forested lands within the 'blue line'.

The 1891 report of the Forest Commission again addressed the idea of an Adirondack Park, and this time recommended a bill to create the park. Again the Commission advocated for lumbering on Forest Preserve lands and for the sale of certain State lands outside the park. The report also referred to the sales of "separate small parcels and tracts" of land taking place under Chapter 475 of the Laws of 1887; with one of the tracts sold in the Adirondacks being a not-so-small 3,673 acres. As far as the Catskills were concerned, the most important part of the report was a recommendation to provide $50,000 to acquire "forest land situated within the counties of Greene, Ulster, Delaware and Sullivan, at a price not exceeding one dollar and fifty cents per acre …" The inclusion of funding for the Catskills, said the Commission, was because the 1885 law "establishing the Forest Preserve, contemplated a reservation in the Catskills .... and not without good reason." This good reason was that state ownership was necessary to protect "the watersheds of our great rivers" and because "the wooded slopes of the Hudson watershed demand special consideration." In making the first written reference to a Catskill Park, the Commission said, "But there are other important reasons for the establishment of a forest park in the Catskills." These other important reasons were that the Catskill Forest Preserve "is in close proximity to the great cities of New York and Brooklyn and many cities along the Hudson. It is easily accessible to three-fourths of the population of the State ... It is a favorite spot with the vast population of New York and Brooklyn on account of its accessibility, cheap railroad fare, and desirable accommodations for people of moderate means."

Chapter 707 of the Laws of 1892 created the Adirondack Park and defined it to be, "All land now owned, or which may hereafter be acquired by the state within" certain listed towns in the counties of Hamilton, Essex, Franklin, Herkimer, St. Lawrence and Warren, and stated that the state lands within the park were to "be forever reserved … for the free use of all the people." Private land was not included in this first definition of the Adirondack Park, and the boundary was primarily for the purpose of specifying an area of the Adirondacks where state land acquisitions should be concentrated. The law repeated most of the provisions of the bill recommended a year earlier by the Forest Commission, including the authority to sell Forest Preserve lands throughout the Adirondacks (but not the Catskills), and also lease lands for private camps and cottages. Governor Roswell Flower, in fact, thought that the State's judicious sale of timber and leases should pay for the maintenance of the Preserve. The new law did repeal Chapter 475 of the Laws of 1887, allowing land exchanges. The law unfortunately did not include the previously recommended funding or authorization for acquiring Forest Preserve lands in the Catskills.

A minor consolation to the Catskills was Chapter 356 of the Laws of 1892, which provided $250 to the Forest Commission "for completing the public path leading to the summit of Slide mountain, Ulster County, included within the preserve …" Townsend Cox, still one of the commissioners, must have hoped the funding would put the "public path" in better shape than when he had traveled it back in 1886. An 1893 budget bill (Chapter 726) provided $1,000, "For the expenses of examination of title and survey of lands owned by the state on Slide Mountain in Ulster County and other parts of the Catskills ..." The $250 "public path" money may not seem of much importance, but it was the first legislation to authorize a recreational trail and is the point of beginning of the present and extensive trail system throughout the Adirondacks and Catskills. The Catskills had a first after all!

The 1893 Forest Commission recognized that the $50,000 recommended for the Catskills in 1892 hadn't survived the legislative process. They didn't believe it proper to continue to discuss "the Adirondack wilderness to the utter exclusion of the interests of the Catskills." They thought some effort should be made to make "a solid tract of … these holdings ... in scattered lots ... by the purchase of additional lands, in order that they can be brought under some systematic management. ... We believe that it would be well to acquire 100,000 acres in the immediate vicinity of the lands mentioned." Accordingly, the Commission recommended a bill to purchase "sixty thousand acres" in the Catskills "at a price not exceeding one dollar and fifty cents per acre ..." As noted, this recommendation did not succeed either.